A Long Lost Friend: Murder and Magic at Southern Pennsylvania’s Hex House

- Brian Goodman

- Jan 20, 2019

- 30 min read

Updated: Aug 4, 2020

Somewhere in south-central Pennsylvania, a family is worried.

A child has fallen ill and shows no signs of improving.

After a fair amount of hand-wringing and soul-searching, a man enters the house to fetch the remedy – not medicine, not a doctor, but a short passage from a small book. Its pages contain neither the telephone number of a trusted physician nor the recipe for a therapeutic elixir, but nonetheless hold a tried and true method of healing.

Quite simply, it’s faith.

Without a word, the man fetches a pot from the kitchen and dips it full of rain water that’s collected in an old barrel by the barn. Back inside the house, he gently places an egg in the pot and slowly brings the rain water to a boil. Outside again, the man paces the yard until he finds what he is looking for – an anthill upon which to place his egg. Before doing so, he removes the sewing needle he’s been carrying between his lips and delicately bores three small holes into the egg.

Relieved his work is done, the man returns to his home to join his wife and sick daughter. He breathes easier knowing her ailment will be lifted once the egg has been devoured by the ants in the backyard.

The mysterious rite carried out by the worried father could have taken place two centuries ago or two weeks ago – such is the enduring practice known as braucherei, powwow, sympathy or simply “trying.”

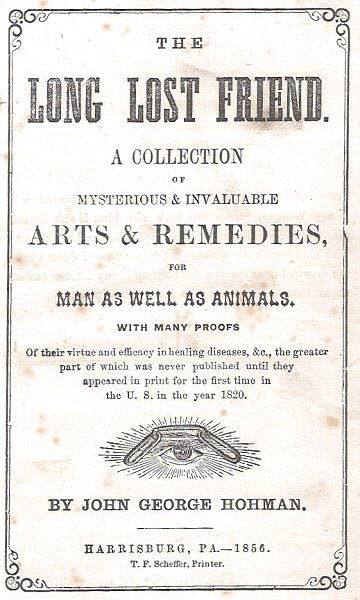

The book, called “Long Lost Friend,” “Der Lange Verborgene Freund” in its original German form or just “Powwows” in later editions, may have come from the bookshelf, the bed stand – where it had a place next to the Bible – or from within a locked cabinet in which it had been long hidden away. Or, perhaps, the book exits only figuratively anymore – its chapters having long since been committed to memory to be called forth at a moment’s notice.

Compiled in 1820 by German emigrant Johann Georg Hohman, later to be known as John George Hohman, “Der Lange Verborgene Freund” is a rambling, hodgepodge of arts, remedies and charms crammed into an unassuming 100-page text.

The best description of “Long Lost Friend” might be arrived at by thumbing through its pages. Listen: “How to make a wand for searching for iron or water,” “A sure way of catching fish,” “To cure the poll-evil in horses,” “To destroy warts,” “To stop bleeding,” “To make good beer,” “To cure the bite of a snake,” “To prevent cherries from ripening before Martinmas,” “To protect cattle against witchcraft.”

It also comes with a remarkable protective charm offered to those who simply carry “Long Lost Friend” around with them: “Whoever carries this book with him, is safe from all his enemies, visible or invisible; and whoever has this book with him cannot die without the holy corpse of Jesus Christ, nor drowned in any water, nor burn up in any fire, nor can any unjust sentence be passed upon him. So help me.”

Given the promise of protection through mere possession of the book and the wide range of remedies and charms it offers for all manner of ills, it is not so surprising Hohman’s original 1820 “Der Lange Verborgene Freund” has never been out of print. It was translated into at least three separate English versions, branched out into dozens of editions of “Long Lost Friend” and can presently, 187 years after its initial publication, be purchased in national bookstore chains, downloaded from the Internet and is even still found in the possession of actively practicing modern witches.

The Coming of Witches

For some, the mention of powwowing might call to mind images of Native Americans dancing around a bonfire with faces painted for battle and spirits entranced in pre-war ritual. The Pennsylvania German practice of powwowing, however, is something quite different.

The occult folk medicine known in Pennsylvania German dialect as braucherei has existed since the 17th– and 18th-century emigration from German-speaking portions of Europe to colonial Pennsylvania. In addition to their families and their language, these people also brought their cultural superstitions and traditional folklore to America – including the European pseudo-medical/quasi-magical concept of sympathetic healing.

How or why it came to be known as powwowing in America remains unknown.

Pennsylvania folklorist Don Yoder, in a 1976 article, said the use of the Algonquin word “powwowing” was most likely transferred by early New Englanders from meaning Indian medicine man to meaning white folk healer. While some still maintain that European healing tradition blended with Indian shamanism in America to create powwowing, Yoder and other scholars disagree.

“The word ‘powwow’ is the only thing Indian about the occult folk healing beliefs and practices of the Pennsylvania Germans,” Yoder wrote.

Etymology aside, powwowing is basically the art of healing – be it by faith, prayer or an eclectic mixture of recitations, charms and superstitious instructions.

“Pow-wowing was essentially a religious movement which regarded illness as the work of the devil, an evil manifestation to be expelled by charms, herbs, manipulations and incantations delivered by an empowered believer in the Scriptures,” Lehigh University professor Ned D. Heindel wrote in the introduction to his book, “Hexenkopf: History, Healing & Hexerei.”

Pennsylvanian author and newspaperman A. Monroe Aurand, in his 1929 work “The ‘Pow Wow’ Book,” concurred.

“Pow-wowing should be considered an attempt on the part of one person to do someone else some good – to heal,” Aurand wrote.

In his book, Aurand pointed out there isn’t much difference between powwowing and other forms of faith healing – most notably prayer in church – and he thought powwowing ought to be at least as effective

“Pow-wow is a misnomer for a practice that is as entirely sound in principle – as sound and practical as are ‘sugar pills’ and some other so-called antidotes for human ills. Pow-wowing is really a psychological condition,” he wrote.

And in that sentence Aurand touched, perhaps, on the underlying secret to the persistence of braucherei in America. But more on that later.

Now that we’ve established how powwowing descended from much older practices of European witchcraft, it’s time to explain how the customs, beliefs and power itself were able to be carried along and passed down from generation to generation in the America.

The Friend

Holding the book in my hands, a few thoughts spring immediately to mind.

It is small and at about 80 pages could probably be read cover-to-cover and returned to a shirt pocket in less than an hour.

It is unassuming – a mottled brown cover bears no word, symbol or design, yet a cracked leather spine, yellowed pages and well worn corners show the small tome has passed through many hands.

Its contents are at once thought-provoking, humorous and jaw-dropping and what was predicted to take less than an hour occupies much of the rest of my afternoon.

It is an early English edition of “Long Lost Friend; A Collection of Mysterious and Invaluable Arts and Remedies for Man as well as Animals” from the 1850s and it has gripped me in the same way it must have taken hold of the people of rural Pennsylvania roughly 200 years earlier.

Thirty years before my copy was translated and reprinted, “Der Lange Verborgene Freund” was first published in Reading, Pennsylvania by Hohman. It quickly became a best-seller.

Yoder calls it “a standard printed corpus of magical charms” and goes as far as to call its author, Hohman, “one of the most influential and yet most elusive figures in Pennsylvania German history.”

History tells us Johann Georg Hohman came to America in 1802, landing in Philadelphia from a vessel that set out from Hamburg, Germany. He, his wife and their son served as redemptioners on a Pennsylvania farm to pay for their passage to America. Before long, Hohman began writing and publishing – everything from the first American version of the Himmelsbrief, or “Letter from Heaven,” to extensive books on household medicine, ballads, spiritual songs and, of course, his infamous powwow book.

Although Hohman calls himself “author and original publisher” of “Long Lost Friend,” saying only that “this book is partly derived from a work published by a ‘Gypsey,’ and partly from secret writings,” Yoder has shown that a large section of his book, perhaps as much as one-third of the entire content, was lifted from the German-language charm book “Romanusbuchlein,” which appeared in Germany in 1788 – just 14 years before Hohman came to America.

Regardless of how or from where he collected his “mysterious and invaluable arts and remedies,” Hohman was the first, or at the very least the best, at compiling the braucherei practices into a single, simple volume.

It has been estimated that more than 150 editions and about a half-million copies of “Long Lost Friend” have been sold since it was first published. Even as recently as 1929, when Aurand published “The ‘Pow-Wow’ Book,” the author was amazed by the persistence of “Long Lost Friend” and said the wide circulation of the book “would startle the uninformed” and that scarcely a week passed by without the estate of the publisher receiving orders for it.

“Thus, after almost 75 years have elapsed since the first printing in English and 109 years after the first edition in German, the subject is still a major one, and aside from the Holy Scripture and the Dictionary, probably no single book in America has had as consistent and lasting a sale as Hohman’s ‘Long Lost Friend’,” Aurand wrote at the time.

Though brief in length and humble in presentation, “Long Lost Friend” was chock full of every superstition, home remedy and wives tale prevalent among the 19th-century Pennsylvania Germans – a veritable cookbook for whatever ailed them.

Heindel called “Long Lost Friend” “the grandfather of all faith-healing books” and pointed out, rather than a medical book, it is “a detailed coverage, 187 recipes, of occult formulae for curing all manner of illnesses, for driving out demons, neutralizing hexes, effecting the return of stolen goods, deworming horses and men, casting spells and extinguishing fires by magic words. In brief, it is ‘white witchcraft’.”

After its initial publication in 1820, “Der Lange Verborgene Freund” was reprinted in numerous German editions before being published in a rare 1846 English version entitled, “The Long Secreted Friend,” which some have guessed Hohman himself translated. A double-chain of independent English translations followed soon thereafter with “The Long Lost Friend” published in Harrisburg in 1850 and “The Long Hidden Friend” published in Carlisle in 1863.

With the help of Hohman’s “Long Lost Friend,” the practice of braucherei lived on and was widely practiced as a matter of everyday life in Pennsylvania during the 1800s.

It wasn’t until the turn of the 20th century that “Long Lost Friend” again played a role in exposing powwowing to the greater populace – this time to the entire world and at the violent expense of one of its practitioners.

Your Hair, Your Book or Your Life

Dressed in his black, buttoned-down shirt and dark jeans, 47-year-old Rick Ebaugh tells me it’s been said he resembles his great-grandfather.

It’s not the phrase itself that strikes me as odd so much as the setting in which the comment is made. We’re standing over a burned out hole in the blood-stained floor of the old Pennsylvania home where Nelson D. Rehmeyer, the infamous witch of Rehmeyer’s Hollow, was murdered almost 80 years ago.

Ebaugh, Rehmeyer’s great-grandson, is looking to right a wrong eight decades old and clear the name of an ancestor he believes was an honest and well-liked farmer – one who happened to have been blessed with the ability to heal.

The family’s story began when two Rehmeyer brothers traveled from Germany to America in the early 1800s looking for a place to settle their family in the New World. Like many other German transplants, the Rehmeyer brothers found themselves in south-central Pennsylvania, which had a thriving Deutsch community. It wasn’t long before the brothers found the hollow – a deep, wide gash in the countryside, surrounded by hills, carpeted by forest and fed by creeks and springs. Recognizing the unique topography of the land, in what is today York County, the brothers decided this was the perfect place for the family to relocate. Word was sent to their family in Germany, who soon boarded a boat headed for America.

After building the family homestead, a sturdy log cabin situated with the hills above and the deepest wet of the hollow below, the Rehmeyer clan began expanding. One cabin soon became two, which soon became a small community of homes through the hollow. The family farmed the land, dug wells, built at least four mills and later even constructed a small general store, which Ebaugh says was eventually converted into a church.

Time marched on, the family grew and by about 1900 a 30-something Nelson D. Rehmeyer built a house alongside the old family cabin in what was by then known as Rehmeyer’s Hollow. By this time Rehmeyer had already established himself as something of a local commodity – practicing powwow for friends and neighbors.

Just like farming, it is likely Rehmeyer learned his powwowing from his father. As the only practicing braucher or powwow doctor in the hollow, Rehmeyer treated many in the community, Ebaugh said.

“That’s how he was with his powwowing. It was always as a favor. There wasn’t any payment,” he added.

Rehmeyer had two children, both daughters, and one of them, Beatrice, raised Ebaugh. As a curious nine-year-old, Ebaugh would often ask his grandmothers to tell him about their father. It was through such stories he learned about the murder of his great-grandfather.

In the course of his unofficial duties as local powwow doctor, Rehmeyer once treated a boy who was suffering from opnema – a wasting away of the body that was believed to be caused by an evil hex, but was more than likely caused by malnutrition. This sickly boy was John Blymire, who would later play significant roles in Rehmeyer’s life; first as his employee and later as his murderer.

Blymire would be afflicted with the opnema again later in his life, but this time, as his life spiraled, he was convinced he was the victim of a hex – his first two children died within days of their birth, his health declined, he lost his job, was divorced by his wife and was eventually committed to a state mental hospital from which he promptly escaped.

In the early days of the 20th century in rural south-central Pennsylvania, superstitious residents knew the only way to combat a hexenmeister, one who used the power of braucherei to curse and harm rather than heal, was to fight fire with fire. So Blymire consulted several local witches and learned he had been hexed by someone close to him.

By 1928, a 30-year-old Blymire had befriended a pair of local teenagers, 14-year-old John Curry and 18-year-old Wilbert Hess, both of whom also believed they had been hexed – exhibited in such bad luck occurrences as failing crops, chickens that wouldn’t lay eggs and cows that wouldn’t produce milk.

As a last resort, the group consulted Nellie Noll, the Witch of Marietta, also known as the River Witch, who told Blymire, for reasons still unknown, that he had been hexed by the Witch of Rehmeyer’s Hollow – Nelson D. Rehmeyer, the man he occasionally worked for and who had healed him decades earlier.

The instructions for breaking the hex were rather simple – all the group had to do was get Rehmeyer’s “Long Lost Friend” witchbook and burn it or get a lock of his hair and bury it six feet underground.

The trio soon hatched a plan, bought some rope and, on Wednesday, November 27th, 1928, the night of the full moon and Thanksgiving Eve, walked through the hollow to Rehmeyer’s house.

At the house, things quickly went sour. The group demanded the witchbook. The 60-year-old Rehmeyer refused. The trio attacked, wrapping a length of rope around Rehmeyer’s neck and wrestling him to the ground before striking him over the head with a block of wood. They had killed the witch of Rehmeyer’s Hollow.

Squinting his eyes and looking at the house, Ebaugh can almost envision how the night played out. His version of the story, however, differs from that told in a York courtroom and involves a premeditated plot to rob his great-grandfather using his widely-known powwowing powers as a convenient scapegoat.

“I’m gonna say, maybe they made it up,” Ebaugh said of the murderous trio. Rehmeyer knew his attackers, having employed them from time to time to work on the farm. They knew he had money and paid well, Ebaugh theorized. As the group spoke and likely drank that night, they unleashed their plot. A beaten and partially bound Rehmeyer was thrown on the floor with mattresses and blankets on top of him, soaked in oil from a nearby lamp and then set ablaze. The trio ransacked the house, took a small amount of money and left as the place was smoldering. They figured the house would burn down and investigators piecing together the scene would find an old man who had been home by himself, plenty of alcohol and an overturned oil lamp – a typically tragic cocktail in the rural days of the early 20th century. But the house didn’t burn down and Rehmeyer’s body was not consumed by flames. A smile actually crosses Ebaugh’s face as he describes what happened in the minutes after his great-grandfather was murdered. As with most criminals, this trio was in a hurry and in their haste they made a costly mistake, Ebaugh said. Racing to get out of the home and allow the fire to do its work, the group apparently wanted to make sure no one could get in or out and latched tight all portals to the outside – securing the home, but also choking off the ventilation and cross-breeze needed to stoke the burning body.

“If they wouldn’t have closed all the doors and shut the windows this place would’ve burned to the ground,” he added.

Ebaugh doesn’t flinch when detailing the gruesome details of his great-grandfather’s demise, in which the blood, melting gristle and other fluids dripping from his body actually doused the fire, saved the house and preserved the crime scene.

“They made a mistake that night,” he said.

The house was scorched, but did not burn. A neighbor passing by on November 30th heard a mule braying and, checking on the unfed animal, found Rehmeyer’s corpse lying on the floor.

It did not take the police long to arrest the trio for the murder; and all three confessed to the crime Blymire said he was at peace with Rehmeyer dead and a lock of the witch’s hair, indeed all his hair, safely buried six feet underground. Thus began the infamous York hex murder trial. It was only a three-day affair, Jan. 7-9, 1929, but was covered by a wildly sensationalistic national media who played up the hex curse and persisting belief in witchcraft among the people of Pennsylvania. The media and its readers around the world were stunned people still believed in witches and hexes and even local cynics, familiar with the still-active practice of braucherei, were at a loss to find any case law when it came to hex killings. “Where, in the history of criminal trials, has there ever been a case where the obtaining of a ‘lock of hair, or a Pow Wow book’ have been such inconceivable and impossible motives for murder?” Aurand wrote. Aurand, who attended and covered the trial along with dozens of other reporters from across the nation and around the world, wrote that at 7:40 p.m. on the third day of the trial Blymire heard the fateful words from the foreman of the jury, “Guilty of murder in the first degree, with the recommendation of life imprisonment.” Blymire was said to have yawned from time to time as he told his story in a “quiet, dispassionate and straight-forward manner,” according to Aurand. A few minutes after the sentencing, Blymire was heard to say “I am happy now. I am not bewitched anymore. I can sleep and eat and I am not pining away.” The 14-year-old Curry was also sentenced to the penitentiary for life and 18-year-old Wilbert Hess was found guilty of murder in the second degree and sentenced to 10 to 20 years in the penitentiary. The Philadelphia Record called the trial “the weirdest and most curiously fascinating in the history of modern jurisprudence.” Although it lasted only a few days, the York witchcraft trial consumed the interest of the nation and forever changed how the traditions and customs of the Pennsylvania German community were viewed – as if it were their own heritage on trial before the disbelieving court of public opinion. In 1934, Hess and Curry were paroled and went on to live quiet lives in the York area. Blymire was finally paroled in 1953, returned to York and worked as a janitor. Each died decades ago with little fanfare.

Rehmeyer is buried near the hollow which still bears his family name and is still called home by many of his ancestors. As for his house, it laid dormant and unnoticed for decades, much like the lingering brauchers in the area, before stirring with life in recent years.

House in the Hollow

Staring into the dark woods behind the house in which his great-grandfather was murdered almost eight decades ago, Ebaugh reveals a little about himself.

He’ll turn 48 this year and just walked away from a 20-year career with an injection mold company. Among his reasons for abruptly retiring was the pursuit of a dream that began with his grandparents and which he’d like to see through to fruition. Ebaugh wants to exhibit the Rehmeyer house – including the spot where his great-grandfather was murdered – and open it up as an historic destination for visitors. It would also give him the opportunity to work on shining up the tarnished image of Rehmeyer and his family.

“I want to go back there. I want to open that house up and show it; I guess you could say, to the world,” he said. Following Rehmeyer’s murder in 1928, the house sat vacant and untouched for years; eventually falling into severe disrepair. “After his death, years passed, trees grew up and the house almost collapsed,” Ebaugh said. Photographs taken 20 years after the murder show a dilapidated house with a porch leaning precariously to one side and a yard overtaken by vegetation. Ebaugh’s grandparents eventually fixed the house up and moved back in. By 1993, they had died and Ebaugh inherited the home in which his great-grandfather was murdered. He rented the house out for several years (it is the renters, Ebaugh blames, for the red “13” adorning the front of one of the garages beside the house) before deciding to slowly return the house to its appearance at the time of Rehmeyer’s murder. For about a half-dozen years, Ebaugh has worked on the house, “taking it back to the time.”

In spring of 2007, Ebaugh, with the assistance of friend Jerry Duncan, decided to push for opening the house to the public. His reasons for wanting to open the house are several – historical preservation; yes, perhaps at some point financial gain; but more than anything else to correct what he believes has been an injustice done to his great-grandfather’s legacy through continued retelling and exaggeration of the tale.

“To set the record straight on Rehmeyer. He was a good man, that’s what I’m really after,” Ebaugh said.

For being the scene of such an infamous event, the Rehmeyer house is rather unassuming. In fact, if not for the incomplete job Ebaugh has done ripping off an old blue-green siding to reveal the original dark wood underneath, one might believe the common rumors that the “Hex House” burned to the ground and drive right past it.

The house consists of three floors – the two rooms on the main level, a basement, a second story and an attic. Entering from the front porch through a red front door, one is standing in the living room, which might be 10-feet by 20-feet. It is adorned by a red sofa and a pair of wooden chairs and features a doorway leading to a similarly-sized kitchen and a staircase leading up to the second floor.

In the kitchen, an awareness of one’s surroundings sinks in as Ebaugh removes a piece of plywood on the floor.

After he was killed and set afire, Rehmeyer’s body burned partially through the kitchen floor boards. Ebaugh has placed a rectangular piece of glass above the hole, which allows visitors to imagine where the fight and murder took place while staring at a charred and bloodstained support beam.

In one corner of the kitchen sits the iron stove, which also served as the furnace and the only source of heat in the home. On the other side of the kitchen, Ebaugh has placed a cupboard and cabinet owned by Rehmeyer at the time as his death. Other furnishings pack the basement and attic or are stored at Ebaugh’s home.

“I have the chairs from the night of the fight,” he said.

Ebaugh would also like to rebuild the original log cabin constructed by the Rehmeyer brothers on the site when they settled there from Germany. The existing house was built beside the log cabin, which later was razed.

Elaborating on his future plans, Ebaugh said he would like to return more of Rehmeyer’s belongings to the house, including the wall clock which famously stopped at 12:01 a.m. – the exact time of the powwow doctor’s murder. He also plans to set up picnic tables in the yard, offer farm tractor tours along the winding paths through the surrounding woods of the hollow and perhaps even stage reenactments of the circumstances leading up to and through the murder.

There are several accounts of the Rehmeyer murder and ensuing hex trial, including Arthur H. Lewis’ 1969 nationally-distributed tell-all account “Hex,” which ended up becoming the seminal book on the topic, and the much more recent “Trials of Hex” published a few years ago by York attorney J. Ross McGinnis.

While he said “Hex” is mostly hogwash and McGinnis hits closer to the truth, Ebaugh stressed there is only one source for the truth.

“There’s only one that can tell you of that night and the whole truth and he’s standing right beside you,” he said.

Since beginning his quest to publicly open the Rehmeyer house, Ebaugh has been contacted by the families of the trio who murdered his great-grandfather. They have photographs of the men, artwork some of them painted while in prison and other items they’d like to be displayed in Rehmeyer’s house.

So what does the descendant of a victim say to the ancestor of a murderer?“Sure, why not? It’s all part of the history,” Ebaugh answered.

“It’s a landmark. It’s [an] historical site. Everybody in the township but one or two people wants to see it happen. I think it’d be great for the community and everybody,” he added.

Unfortunately for Ebaugh, the “one or two people” who don’t want to see the Rehmeyer hex house opened to the public are among the North Hopewell Township officials who have a final say in the matter.

In early August, a request to open the house as an historic site with Ebaugh serving as its curator was denied. There are confusing currents swirling in the case which involve small town politics, the sentiments of those who want to embrace and relive the long suppressed customs of the Pennsylvania Germans and the resistance of those who want to forever bury them.

Ebaugh, who was preparing for a September zoning variance hearing on the matter, can’t understand the opposition.

“I’ll just say, what could be the reason you don’t want this to open? We’re going to pursue it and open it one way or another,” he said.

So why is there a power struggle over the future of the Rehmeyer house and whether powwowing will be introduced to a new generation? What is it about braucherei that shamed many of its practitioners into burning their copies of “Long Lost Friend” following the York hex murder trial and led remaining powwow doctors to slink away into seclusion? Why would the judge in the hex murder trial refuse to let the word “powwow” even be mentioned in his courtroom?

Perhaps it’s because powwowing really works.

Proof of Power

Imagine if it were illegal for a vendor to sell a rabbit’s foot on a keychain if the purchaser didn’t immediately win the lottery or experience a similar dose of good luck.

Or if the state prosecutor’s office opened up an investigation into your business if tipped off by a ticked off customer that a horseshoe purchased from your shop didn’t shower the household with blessings when displayed in the home.

Such was the case presented in the “Medical Practices Act of Pennsylvania,” which came about in 1911 and stated, according to Aurand’s summation, that “if certain members of the State Medical Board, or any physician, for that matter, should take exception to the pow-wow doctor’s practices, they have the law of the Commonwealth to support any actions they want to take.”

Essentially, any licensed medical practitioner in Pennsylvania could turn in a powwow doctor if they believed he or she was doing more harm than good – or if they just wanted to put the braucher out of business and take over all of his regular paying clients.

The tide seemed to be turning against powwowing in Pennsylvania even a decade before the Rehmeyer murder trial sounded what many believed was its death knell.

Under the “Medical Practices Act of Pennsylvania,” the mere acceptance of a fee for any powwow services rendered became the sticking point and could lead to arrest and conviction of the powwow doctor.

The act was fueled largely by several deaths attributed to powwow doctors because it was deemed proper medical attention from a licensed practitioner could have cured the ultimately fatal ailment. In one memorable instance, a three-month old child died, ostensibly from malnutrition, but had been treated expressly by a powwow doctor for opnema, or “take-off.”

But the real outrage was not in the few scattered deaths attributed to powwowing. It was in the reality that braucherei had not only managed to survive into the 20th century, but had actually grown into a rather profitable venture which chewed up much of the business and paying customers from an infuriated class of licensed doctors.

In short, people continued to flock to brauchers because their powwowing, in some cases, worked as well as the medicines offered by the licensed doctors.

The first proof of the apparent efficacy of braucherei comes in the introduction to “Long Lost Friend,” in which Hohman rattles off a list of testimonials more than three pages long from those healed through powwowing.

“The daughter of John Arnold scalded herself with boiling coffee; the handle of the pot broke off while she was pouring out coffee, and the coffee ran over the arm and burnt it severely. I was present and witnessed the accident. I banished the burning; the arm did not get sore at all, and healed in a short time. This was in the year 1815. Mr. Arnold lived near Lebanon, Lebanon County, Penn.,” Hohman wrote.

There are not, of course, any testimonials provided from those for whom powwowing was not successful, but the list of ailments – eye injuries, sores and even convulsions – healed by powwowing is lengthy, and Hohman challenges any who would call him a liar.

“If any one of the above named witnesses, who have been cured by me and my wife through the help of God, dares to call me a liar, and deny having been relieved by us, although they have confessed that they have been cured by us, I shall, if it is at all possible, compel them to repeat their confession before a Justice of the Peace,” he wrote.

A century later, in 1929, Aurand quoted several instances of powwow in action – a judge who witnessed powwow used to staunch the flow of blood, a man who carried “Long Lost Friend” with him for 16 years and never befell an accident until after he lost the book. Aurand also interviewed an old powwow doctor, who alleged to have cured everything from blisters to deafness.

But in the same breath Aurand asked, “How many persons who believed in pow-wowing have been ‘cured’ is not known to mortal man; nor how many have been ‘cured’ proportionately by the ‘sugar pills’ provided by the medical man.”

Unfortunately, there is no way to verify any of these accounts of so-called sympathetic healings or braucherei. But that hasn’t stopped at least one man from trying.

“Right now, I can tell you that the evidence suggests that powwow patients have experienced some benefit after being powwowed,” anthropologist and author, David W Kriebel, Ph.D., said in an email interview.

For his 2002 essay, Powwowing: A Persistent American Esoteric Tradition, Kriebel researched powwowing by performing ethnographic fieldwork in Adams, Berks, Bucks, Lancaster, Lebanon, Lehigh, Montgomery, Schuykill, and York counties in Pennsylvania. He made some startling discoveries about the supposedly extinct practice.

Tracking down existing powwowers and powwow clients was difficult for several reasons, Kriebel wrote. Fewer than half of those he interviewed had even heard of powwowing and those who had were reluctant to discuss it for fear they would be labeled crazy or worse. Kriebel also found a substantial religious opposition among those who consider powwowing to be the work of the devil – even though they occasionally ask God to heal through prayer.

Undeterred, Kriebel was able to find information on at least seven living powwow doctors in southeastern and south-central Pennsylvania and rumors of perhaps another dozen practicing in the region. He also collected evidence using nearly a hundred 20thcentury cases of powwowing and dozens of survey questionnaires on braucherei.

What Kriebel found in his analysis was that, out of 89 cases in which the outcome of the treatment was known, “healing is reported to have occurred in 80 of them, a success rate of 90 percent,” he wrote.

The possible explanations for such a high success rate in the powwowing he studied include everything from the placebo effect to “healing through supernatural intervention.”

“As I have said before, the mechanism for this is not understood. Some of it could be spontaneous remission, some could be placebo effect (although that would not explain cases in which animals were healed), some could be concurrent, but unreported (or forgotten) treatment from another source, some could be exaggerations of its effectiveness (not implying dishonesty, but merely faulty memory), and some of it could potentially be due to some other process. Of course, powwowers today would credit God for this. But that may be beyond the limitations of science to evaluate,” Kriebel said in his email.

In one instance, Kriebel, whose new book, “Powwowing Among the Pennsylvania Dutch: A Traditional Medical Practice in the Modern World,” was published in late August, experienced the effectiveness of powwowing first hand.

When visiting a Schuylkill County powwower, who instructed him to face east and hold a Bible while she drew symbols on his body and “wiped off” his arthritis affliction, Kriebel said the woman told him she sensed a pressure behind his eyes.

According to Kriebel, “she did correctly forecast a migraine that came on within minutes of leaving her house.”

So what can be healed by braucherei? Perched on the porch of the house in which his great-grandfather was killed for such practices, Ebaugh is quick to rattle off a list.

“Take warts away; if you have a temperature or are real sick for a day or so or if you can’t eat anything; leg pains; arthritis,” he said. “I’ve seen old people do them. They rub your leg and mumble a couple words.”

Ebaugh said powwowing was performed in conjunction with the moon and stars and, when visiting a powwow doctor, patients were usually told to come back at a certain time and date, when the astrological signs would allow healing, or the braucher would simply perform the healing from afar when the signs were right and inform the patient their ailment would begin to resolve itself within the month.

Through the course of the interview, Ebaugh continues to drop not-so-subtle hints his involvement in braucherei may extend beyond interest in a murdered ancestor.

Pointing to what has become about an acre of scrubland, Ebaugh said Rehmeyer used to raise herbs in a garden to use in his powwow remedies. Like his great-grandfather, Ebaugh also grows herbs “for concoctions” at his home.

“Things people go to the doctor for; I can do at my house,” he said.

In a further display of powwow knowledge, Ebaugh drops to one knee when rounding the corner of the Rehmeyer house.

“Do you know how to get rid of freckles on the face of a kid?”With a cupped hand, Ebaugh quickly collects a palm full of morning dew from a patch of clover and splashes it onto his face as if he is applying aftershave. The next time we meet I’ll have to remember to check his complexion.

In clarifying the astounding 90-percent powwowing success rate he found in his analysis, Kriebel admitted more than one-third of the successes were of minor ailments, such as warts, which are known to resolve themselves over time, or culturally-defined maladies, like opnema and wildfire, known only to the Pennsylvania German culture.

Cultural conditioning and spontaneous remission aside, if powwowing works and has been proven to work since well before Hohman put pen to paper on the topic, what are they chances it will live on and heal future generations of believers?

Generation Hexed

Ebaugh admits he doesn’t dream often, but said when he does he has strikingly realistic visions of events he finds often come to pass. He shrugs off suggestions his great-grandfather’s braucherei talents may have worked their way down the family tree.

When pressed for an example of his visions, Ebaugh mentions the name of an elderly woman who lives in the hollow and whose parents were occasional recipients of Rehmeyer’s powwow remedies and healing.

On a visit to her house while she was on vacation, Ebaugh was hit with a sudden sense of danger as he placed his hand on her doorknob. Later that night, Ebaugh dreamt of a car swerving severely on a roadway and only narrowly avoiding disaster. When the woman returned from her trip, Ebaugh asked her if anything unusual had befallen her on a roadway during her travels. He was unsurprised when she told him of how a vehicle blew a tire on a highway, which nearly led to a high-speed collision.

Reminiscing back to his childhood for another instance of his “sight,” Ebaugh recalled when he was only about 12 years old, living with his grandparents not far from the Rehmeyer house in the hollow.

The young Ebaugh was startled by the scent of some burning material inside the home and alerted his grandfather to the danger. While his grandfather couldn’t smell the smoke, both raced around the house looking for anything smoldering. Outside the home, the pair continued to look for the fire, but Ebaugh noticed the smell of the smoke faded outdoors.

Not long thereafter, the telephone rang. It was a co-worker of his grandmother’s informing them her car had caught fire while she was at work – well out of range of young Ebaugh’s nose.

More recently, Ebaugh said, he’ll be sitting in his own home, also in the hollow, and get the sudden sense to check on the nearby Rehmeyer house, only to find trespassers or would-be vandals on the porch.

“Even now I pick up different things. I just don’t tell anyone about them,” he added.

Ebaugh believes there may be a connection between his own visions and his great-grandfather’s powwowing, but he deflects any questions about his own possible practice of braucherei.

“Let’s say, I’ve many a time had the books in my hands,” he said.

Perhaps to change to topic, or in his own way answer the question, Ebaugh fishes into his jeans and pulls out his great-grandfather’s pocket watch. He went through great expense to get the watch polished and again ticking. It is always in his pocket.

To his knowledge, there is still one powwow doctor in the area, “although he is getting up there in age,” a couple brauchers in Lancaster and at least one hexenmeister, “who you could still call a witch.”

“I’ve seen everything from faith healing, or what you would call powwowing, to what you would call a witch,” Ebaugh said without flinching.

While none of them advertise, Ebaugh said it is particularly difficult to find the latter, and more sinister of the group. The real witch doctor he knows of can only be tracked down by contacting the right people and arranging a meeting place. While all powwowers invoke the word and power of God in their practice, the hexenmeister uses such power to curse rather than bless.

Describing with such detail as if he might have seen it first-hand, Ebaugh said the home of a witch doctor typically has no electric lights, but is lit by many burning candles arranged in a single room. The average session with a hexenmeister involves the client describing his or her situation and what they would like done to avenge a perceived wrong-doing – usually by placing a hex on someone else.

Ebaugh won’t say how it is that he can so vividly describe an encounter with a witch doctor, but when asked if hexing can work just as effectively as healing, he clenched his jaw, made direct eye contact for the first time during discussion of the topic and answered with two short words.

“It did.”

Unlike the novelty it has become today, Ebaugh said powwowing used to be a part of everyday life in the hollow, where Rehmeyer was the only source of medical expertise for miles.“He couldn’t cure cancer, just like today, but if he could say a couple words out of the book, talk to you a little bit and if you walked away believing he could help you, what’s the harm?” Ebaugh said.

And just like that, Ebaugh let slip one of the secrets of the sympathetic healing of the powwowers.

“Just like anything, you’ve got to kind of believe in it,” he added.

That reminds me of how, before anthropologist Kriebel was treated by the powwow doctor who accurately predicted his oncoming headache, she asked if he believed in God.

For powwowing to work, it seems both the braucher and the patient must maintain an implicit belief that healing will occur. Any doubt in the mind of either the practitioner or the recipient of the faith healing could scuttle the attempted powwow.

With the old generation of brauchers “about all dead,” according to Ebaugh, and given the increasing cultural apathy of our 21st century, is it possible to still find such belief?

Is the extinction of powwowing being accelerated not only because its practitioners are dying off before they can pass the power on to an uninterested generation, but because fewer people actual believe in such faith healing nowadays. With less belief, there are fewer people willing to even test the waters of braucherei and the few skeptics who do approach a powwower may be met with less than stellar results, perhaps as a result of their own unwillingness to believe.

Nelson Rehmeyer’s timepiece may have stopped the moment he was murdered, but for the Pennsylvania German practice of powwowing, the clock is still softly ticking.

Kriebel believes powwowing may be well on its way out, but it is not yet gone.

“The interest in the practice shown by children and grandchildren of active powwowers suggests that the practice will persist in southeastern and central Pennsylvania in some form for at least two more generations,” Kriebel wrote in his essay.

“Its future is uncertain after that, but I would not want to forecast its disappearance at any particular point. Thus far, to paraphrase [Mark] Twain, reports of its demise have been greatly exaggerated.”

In his research, Kriebel found that some elements of braucherei, such as the use of charm books and powwowing for purposes other than healing, have vanished in the last century, but “the core of the practice remains the same.”

“Powwowing, despite repeated claims of its imminent or actual disappearance during the past century, remains a viable health care option among the Pennsylvania Dutch at the dawn of the twenty-first century.”

What’s more, Kriebel accurately points out, powwowing seems to have survived what might have been its roughest patch, “the program of ‘scientific education’ adopted after the York Witch Trial and the attendant stigmatizing of powwowing in the wider region.”

In a small pamphlet he put out in the 1940s entitled The Realness of Witchcraft in America, Aurand relates a story which had appeared a few years earlier in a Harrisburg newspaper.

“State educators declared here yesterday that hexerei, terror of numerous rural farm communities for many years, is being banished from Pennsylvania by the public schools.”

The story goes on to describe how educators planned on using instruction of the sciences as “the most effective weapon against superstition.”

Yoder wisely pointed out that there is value in preserving the very things the York hex murder trial inadvertently and the state of Pennsylvania deliberately tried to eradicate.

“The charm literature in particular can demonstrate to modern-day Americans, lost in their identity crises, the vital importance of our ancestral folk cultures, where the individual was subsumed under the community, where healing was related to faith and sympathy and community integration, he wrote.”

The re-education has been quite thorough, but may not have been enough to completely wipe out the memory and practice of powwowing.

Generations of Pennsylvanian school children have been taught to abandon the cultural quirks and traditional nuances of their German heritage and, even today, tourists to Lancaster, the heart of “Pennsylvania Dutch” country, are told the colorful geometric images on the popular hex signs adorning barns and homes have no real significance beyond aesthetics.

It’s worth noting that the closest neighbor to Rehmeyer’s house, a small cabin a couple bends and a few minutes down the road, has an old blue, white, yellow and red hex sign hanging on the face of the house between a window and a door.

Those still trying to suppress powwowing would tell us the decoration was chosen simply to beautify the otherwise plain cabin and not because of any purported ability to ward off hexes and other curses. Given the proximity of the residence to the notorious “Hex House,” is there any question why a hex sign adorns the house rather than something like a wreath or a pink flamingo?

Long Lost Indeed

With the fate of Pennsylvania German powwowing left largely up to the historic preservation efforts of Ebaugh and others as well as relying on the interest of a youthful generation, there remains one final mystery yet to be solved in the York hex murder case.

There is great confusion and misinformation when it comes to the whereabouts of Rehmeyer’s witchbook – “Long Lost Friend”. York attorney and author McGinnis claims he has the victim’s powwow book, but is tight-lipped on details and outright refuses to say how he came to acquire it.

Ebaugh says others have come forward in the decades since the murder to announce they have Rehmeyer’s copy of “Long Lost Friend,” which would undoubtedly carry great worth as both a macabre memento and historic relic of the internationally-publicized trial.

He merely smirks at the notion.

As Ebaugh tells it, when word of the murder spread just after Thanksgiving 1928, Rehmeyer’s daughters raced from their nearby homes through the woods to the murder scene and removed some of their father’s belongings before the FBI arrived.

Among those items removed prior to the investigation were Rehmeyer’s books, including the copy of “Long Lost Friend,” which had allegedly triggered his murderers into action in the first place. Ebaugh says his family wasn’t looking to compromise the crime scene, but recognized the investigators would have held the books with high suspicion and the family heirlooms would likely have been taken from them forever.

Were he a betting man, Ebaugh would wager Rehmeyer’s “Long Lost Friend” is sitting right where it was taken almost 80 years ago along with a number of other items removed from the home – in the attic of his grandmother’s house where he was raised.

Ebaugh is coy when asked if he knows the precise location of the book. He insists he hasn’t been into the attic to specifically look for his great-grandfather’s powwow books, but also speaks with certainty in his outright dismissal of the claims of the other supposed owners.

“I think that book’s in my possession yet.”

There is also the little matter of the “big surprise” Ebaugh is promising for the grand opening of the Rehmeyer “Hex House.”

Comments